The Third Ladybird Book of British Birds – #16 The Curlew

I’m currently reading the third volume of the Ladybird Book of British Birds and their nests from the 1950s.

Times have changed for the Curlew:

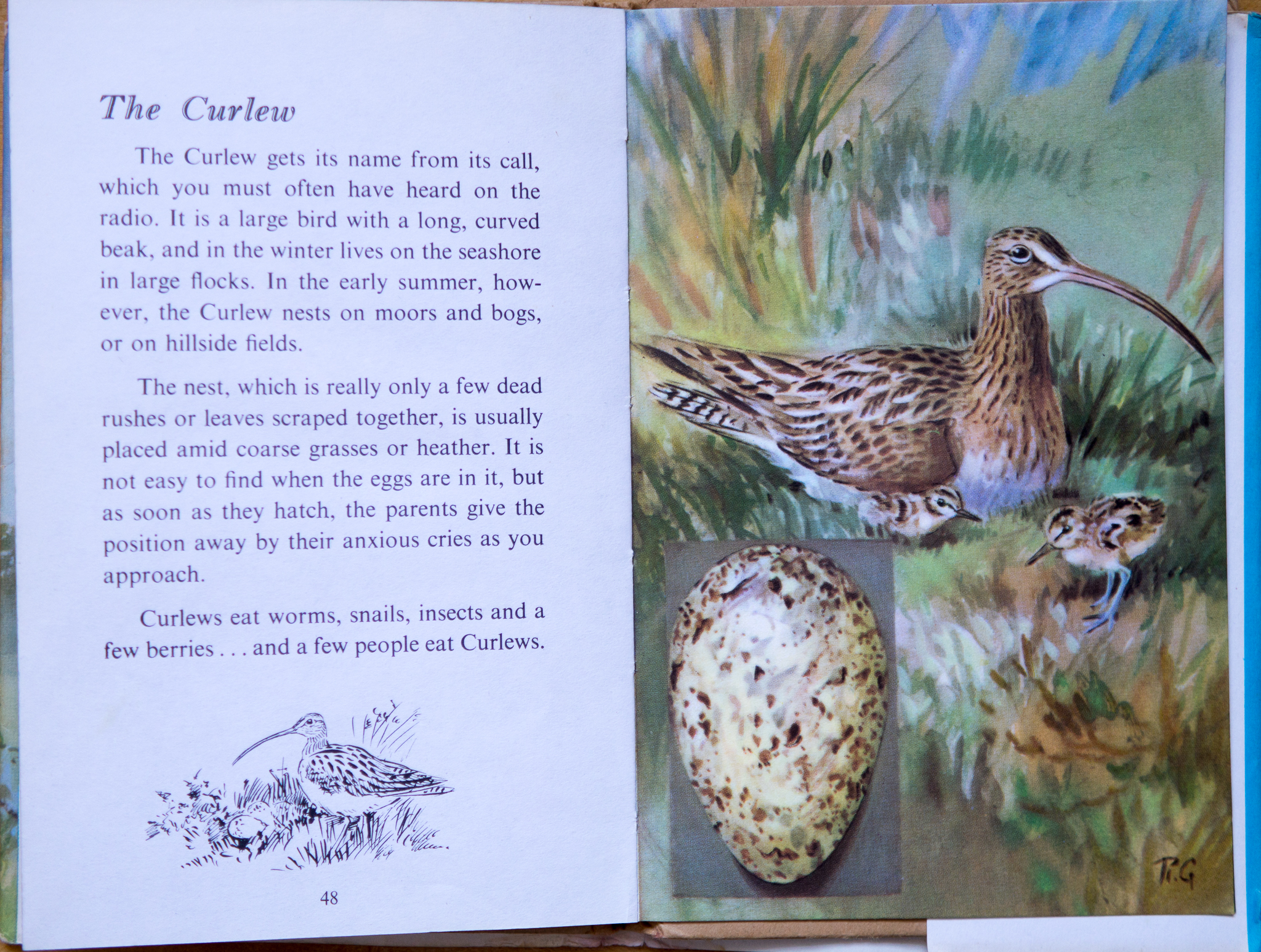

The Curlew gets its name from its call, which you must often have heard on the radio.

Okay, I’m going to need some help here, from someone who knows their bird cultural history or was alive in the UK in the 1950s and who knows why the Curlew’s call was often heard on the radio.

It is a large bird with a long, curved beak, and in the winter lives on the seashore in large flocks. In the early summer, however, the Curlew nests on moors and bogs, or on hillside fields.

I’d love to see a ‘large flock’ of Curlew. We’ve halved their population here in the last 25 years and almost eradicated them from Northern Ireland entirely. There are only a few hundred pairs of Curlew in the south and midlands of England.

The nest, which is really only a few dead rushes or leaves scraped together, is usually placed amid coarse grasses or heather. It is not easy to find when the eggs are in it, but as soon as they hatch, the parents give the position away by their anxious cries as you approach.

I’ve heard those anxious cries on Westray:

Curlews eat worms, snails, insects and a few berries . .. and a few people eat Curlews.

People certainly did eat Curlews. King Charles I tucked into 11 for dinner in 1625:

That’s historically a small part of the reason their numbers are under such pressure. Changes made to land by farmers, including draining wetlands, and intense grazing by animals for meat as well as house-building have all added to their lack of success in raising families. Another is having 13 million inbred domestic dogs in the UK, allowed off-lead in National Parks, nature reserves and moorland areas.

Who cares enough about Curlews to revolutionise the ownership and use of land, what they eat and how pets are kept? Too few people.

More Curlews

Curlew in flight The brief warmth of the sun in the afternoon on a cold day was a welcome interlude on a trip… read more

Curlew in flight The brief warmth of the sun in the afternoon on a cold day was a welcome interlude on a trip… read more A curly Curlew Having a Curlew fly over is always a thrill, especially if I can hear it call. It's the haunting last… read more

A curly Curlew Having a Curlew fly over is always a thrill, especially if I can hear it call. It's the haunting last… read more Whaup on a stab There's a Curlew on a fence post, or, as Orcadians might say, a Whaup on a stab. I've slowed the… read more

Whaup on a stab There's a Curlew on a fence post, or, as Orcadians might say, a Whaup on a stab. I've slowed the… read more Curlew flypast A chance encounter with a Curlew always improves my day. They're my emotional connection to the wilderness we've lost. read more

Curlew flypast A chance encounter with a Curlew always improves my day. They're my emotional connection to the wilderness we've lost. read more The divine right of kings and wildlife on the menu I've discovered the fabulous menu of a dinner fit for a king, eaten in 1625, served in a local house… read more

The divine right of kings and wildlife on the menu I've discovered the fabulous menu of a dinner fit for a king, eaten in 1625, served in a local house… read more Whaup in Buttercups Whaup is the Orcadian name for the Eurasian Curlew, Numenius arquata. Here's one flying above the Buttercups in Westray: They're… read more

Whaup in Buttercups Whaup is the Orcadian name for the Eurasian Curlew, Numenius arquata. Here's one flying above the Buttercups in Westray: They're… read more Curlew It's a warm evening, bathed in orange light. I hear the call first. Then it's the flypast. It's a Curlew.… read more

Curlew It's a warm evening, bathed in orange light. I hear the call first. Then it's the flypast. It's a Curlew.… read more Last call of the Curlew Every time I mention that Curlews are threatened, that their populations are collapsing, that several of the species worldwide are… read more

Last call of the Curlew Every time I mention that Curlews are threatened, that their populations are collapsing, that several of the species worldwide are… read more Grass Snakes, King Curlews and their Lapwing attendants Any patch of good weather means there's a chance of cutting hay for silage. The people of Westray have perfected… read more

Grass Snakes, King Curlews and their Lapwing attendants Any patch of good weather means there's a chance of cutting hay for silage. The people of Westray have perfected… read more