Vernon’s Half-Mourner

I’m in the far south of Italy, in the heel of the boot that makes the Country so much more recognisable than most of the others in Europe. I’m in the garden of a fine manor house. We’re staying in the stables and just to the side of us, with beautiful almond trees and views of ancient stone houses, is a meadow. Wandering with my camera I see a white butterfly and know straight away this is no ordinary white butterfly. It’s got the familiar white and black upper wings but strange and beautiful green patterned underwings. It’s small and definitely not a Green Veined White. Could it be I wonder? Could it be?

I have a closer look.

I hot-foot it back to my laptop and search for the Bath White. I look at UK Butterflies: “Bath White, Pontia daplidice,” it says, “This is an extremely scarce immigrant to the British Isles and, in some years, is not seen at all.” Extremely scarce, wow! “However, on occasion, it does appear in large numbers, such as the great immigration of 1945.” The great immigration! What a classic phrase for finding a few butterflies. “The first specimen was recorded in the British Isles in the late 17th century. Between 1850 and 1939 there were very few records, with only a few years reaching double figures.” It continues: “This species has been extremely scarce ever since with less than 20 individuals recorded since 1952.”Extremely scarce! Excellent. I’ve found a rarity! Hold on a minute though; I’m in Italy.

Let’s see what Wikipedia has to say about it: “It is common in central and southern Europe, migrating northwards every summer, often reaching southern Scandinavia and sometimes southern England.” Oh. That does make a mockery of the idea of finding something scarce. It’s common here. Rather than it being exciting to see it in England we should think that it’s sad that they are lost, doomed and blown seriously off course and will never survive our winter. There are also going to be far more rarities seen in the UK in the next few decades with global warming affecting our climate. If we carry on burning millions of years of fossil fuels in a few decades then we can expect mosquitos in a subtropical swamp in Slough. That might, of course, improve it.

UK Butterflies continues: “The butterfly was originally known as “Vernon’s Half Mourner” after the first recognised capture by William Vernon in Cambridgeshire in May 1702, although earlier records are now known. However, the common name of this butterfly comes from a piece of needlework that figures this species, supposedly showing a specimen taken in or near Bath in 1795, and the name seems to have ‘stuck’.”

Then I remember, I’ve seen that butterfly. The one William Vernon killed in 1702. Yes, the actual one. The incredibly rare visitor which sometimes never makes it to England. A beautiful insect killed, pinned and mounted in its prime. I know I’ve seen it. It’s in Oxford. A little more research and I remember fully. It’s the butterfly specimen that is the oldest preserved mounted insect specimen in the world and it’s in the Hope Collection in Oxford. Here’s what the Guinness Book of World Records has to say about it:

“The oldest known pinned insect specimen, still on its original pin, is a Bath White butterfly (Pontia daplidice), which was collected near Gamlingay, Cambridgeshire in May 1702. The specimen was donated to the Hope Entomological Collections of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Oxford, UK in 1906 and has remained there ever since. Although there are older insect remains in existence, such as those recovered from archaeological sites such as Egyptian tombs, the Bath White is the oldest insect collected and pinned as a natural history specimen.”

The Hope Collection in Oxford has the original 1702 specimen and I’ve seen it as part of a behind-the-scenes introductory tour of the department when I started my animal biology degree at Oxford. “Within the United Kingdom, the Hope Entomological Collections are second in size and importance to the national insect collection at the Natural History Museum, London. The collection houses over 25,000 arthropod types, and comprises over 5 million specimens.” That seems tragic to me, not just because of the needless loss of life, but because many of the species are now completely extinct or extinct varieties or are no longer present in their former range because of widespread habitat destruction.

My butterfly would be extremely scarce if it was somewhere else. Here, it’s just common.

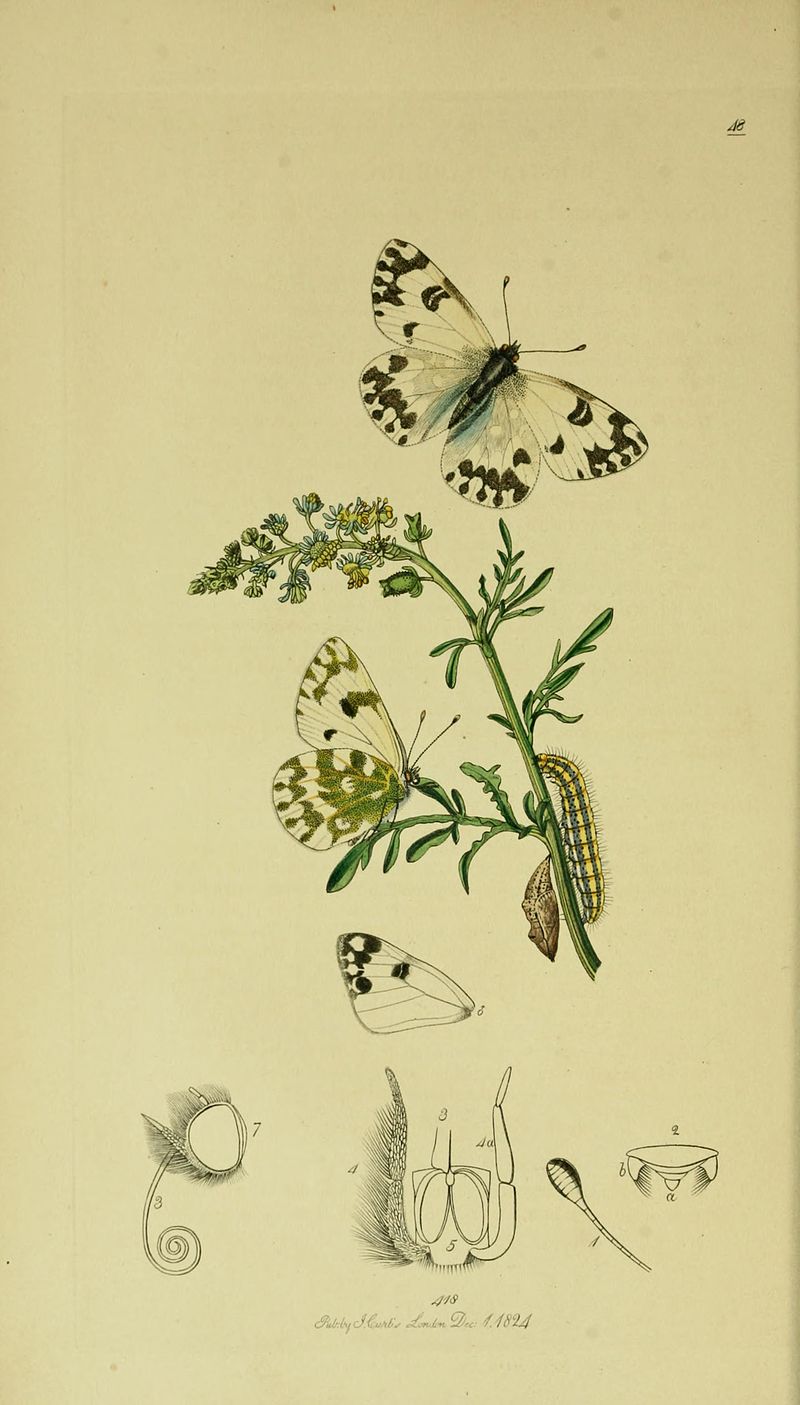

Here’s the Bath White from John Curtis’s breathtaking book ‘British Entomology: Being Illustrations and Descriptions of the Genera of Insects Found in Great Britain and Ireland: Containing Coloured Figures from Nature of the Most Rare and Beautiful Species, and in Many Instances of the Plants Upon which They are Found, Volume 5’, with an illustration from 1824:

Vernon’s Half-Mourner? It’s me who’s in half-mourning for the loss of so much wonderful wild wildlife habitat in such a short time.

More Butterflies

It’s all in the details I love walking around the Vatican Museum. It's great to see the treasures that were accumulated while the majority of… read more

It’s all in the details I love walking around the Vatican Museum. It's great to see the treasures that were accumulated while the majority of… read more Eastern Dappled White Butterfly There are butterflies galore in Broken Tower Meadow, il Pratone di Torre Spaccata. Here's one. I think it's the Eastern… read more

Eastern Dappled White Butterfly There are butterflies galore in Broken Tower Meadow, il Pratone di Torre Spaccata. Here's one. I think it's the Eastern… read more 2022 highlights of a wilder Italian life (part 2) Being able to explore a natural world with different, unfamiliar species is a privilege. It was a thrill to visit… read more

2022 highlights of a wilder Italian life (part 2) Being able to explore a natural world with different, unfamiliar species is a privilege. It was a thrill to visit… read more A Silver-Washed Fritillary I took a photograph of this Silver-Washed Fritillary, Argynnis paphia, this summer in Italy. They are astonishingly fast, have pointed… read more

A Silver-Washed Fritillary I took a photograph of this Silver-Washed Fritillary, Argynnis paphia, this summer in Italy. They are astonishingly fast, have pointed… read more Flutterbyes Here's a flying Swallowtail butterfly, Papilio machaon: It's a little tattered but beautiful all the same: Here's a perfect example… read more

Flutterbyes Here's a flying Swallowtail butterfly, Papilio machaon: It's a little tattered but beautiful all the same: Here's a perfect example… read more Egg-Laying I've enjoyed being amongst the butterflies in Parco della Caffarella. There are many different species and it's great to see… read more

Egg-Laying I've enjoyed being amongst the butterflies in Parco della Caffarella. There are many different species and it's great to see… read more Have you ever seen a photograph like this? I've seen a lot of photographs of butterflies but never one like this. It's not just that it's a shot… read more

Have you ever seen a photograph like this? I've seen a lot of photographs of butterflies but never one like this. It's not just that it's a shot… read more Orange and yellow This Orange-Tip, Anthocharis cardamines, is a beautiful spring sight, especially when feeding on an intense yellow dandelion. Have you seen… read more

Orange and yellow This Orange-Tip, Anthocharis cardamines, is a beautiful spring sight, especially when feeding on an intense yellow dandelion. Have you seen… read more Clouded Yellow This yellow butterfly is such an attractive species. It's a Clouded Yellow, Colias croceus. It's flying in Italy in winter… read more

Clouded Yellow This yellow butterfly is such an attractive species. It's a Clouded Yellow, Colias croceus. It's flying in Italy in winter… read more