Give ’em enough Phalarope

It’s another day on Westray and another chance to walk the cliffs and paths of the island. I’ve got the usual camera with a telephoto lens in my hand, and a flask of tea and a Tunnocks caramel wafer biscuit in my rucksack. It’s summer in Orkney so I’m dressed for 13 degrees less windchill, and kitted out with full camouflage waterproofs and an Arctic hat. Perfect. I’m also surrounded by the usual cast of characters, Bonxies (Great Skuas), Scooty Allans (Arctic Skuas) and Pickieternos (Arctic Terns). I”m going to have a look in one of the pools of fresh water that gathers wading birds. Maybe I’ll be able to photograph a Dunlin?

As I crawl up to the pool on hands and knees I can see Dunlin. That’s very exciting. Then I spot a bird I don’t recognise and forget all about Dunlin. It’s bright ginger-red:

What a stunner. It’s wildly energetic, frenetic, even. It has a beautifully patterned back, a black-tipped yellow beak and a large white patch on its head. What on Earth is it?

I have no phone signal and my bird identification book is too big and heavy for my rucksack. It reminds me of the Red-Necked Phalarope I saw on Westray a few years ago, but it’s a much more powerful, thicker-set bird. Here are my adventures seeing that one:

I know that many wading birds have extreme breeding plumage. Birds like the much larger Black-Tailed Godwits turn a lovely orange in the breeding season.

I know it’s not a species I recognise. It’s also not used to seeing people, as it’s quite happy in my presence. “Must be an Arctic breeder”, I think.

It’s content here, feeding on freshwater crustaceans and aquatic insect larvae. What does make this mystery bird fly is a Scooty Allan sortie overhead, when it wings powerfully away. It’s clearly not stupid, although maybe it was just following the Dunlin flock’s lead.

Thankfully, it comes back.

It has flanges on its toes, just like a Coot, rather than webbed feet. It clearly spends a lot of time swimming or walking on pond weeds; one of the two.

I’m with it for a couple of hours in beautiful light; just me, the island and a beautiful bird feeding and preening in the water. I take hundreds of photographs. I have time to drink the entire flask of tea and eat my Tunnocks while I’m sitting with it.

When I get back home and start developing the images, I’m delighted. I get my bird book out. I’ve got Britain’s Birds, the Wild Guides book. On the opposite page to the Red-Necked Phalarope, which I recognise, is a bird called the Grey Phalarope. That’s my bird.

“Rare but regular autumn migrant (400-600 per year); very rare in spring, winter”, it says. What about summer? “ADULT BREEDING (very rare) orange-red, back streaked black and buff; head black with broad white cheek (Female brightest).”

I’ve found a very rare bird.

Okay it’s an adult breeding-plumage female Grey Phalarope, Phalaropus fulicarius. It’s a bird which is almost never seen. It breeds in the Arctic and winters out in the ocean off West Africa or Chile. It heads straight out to sea from the Arctic and doesn’t come back to land at all until it’s time to breed again. In North America, they are known as Red Phalaropes, because of their orangey-red breeding plumage. It’s very rare to see it like this in the UK. It’s rare to see it like this anywhere. Bird Guides says, “Adult female Grey Phalarope in summer plumage is perhaps the most beautiful of all phalaropes, but is sadly near-impossible to see without a trip to the High Arctic.”

It’s a near-impossible bird to see here.

Bird Guides’ handy photo ID guide to Phalaropes continues:

“In Britain it is encountered almost exclusively as a mid- to late-autumn migrant, most often at sea in the west, but it also occurs as a storm-blown visitor to coastal and even inland waters anywhere. As a result, this species is incredibly rare in Britain in breeding plumage.”

Incredibly rare.

I find the earliest mention of the Red Phalarope, which is from 1750, in A Natural History of Uncommon Birds by George Edwards:

Edwards, George (1750). A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Vol. Part III. London: Printed for the author at the College of Physicians. p. 142, Plate 142.

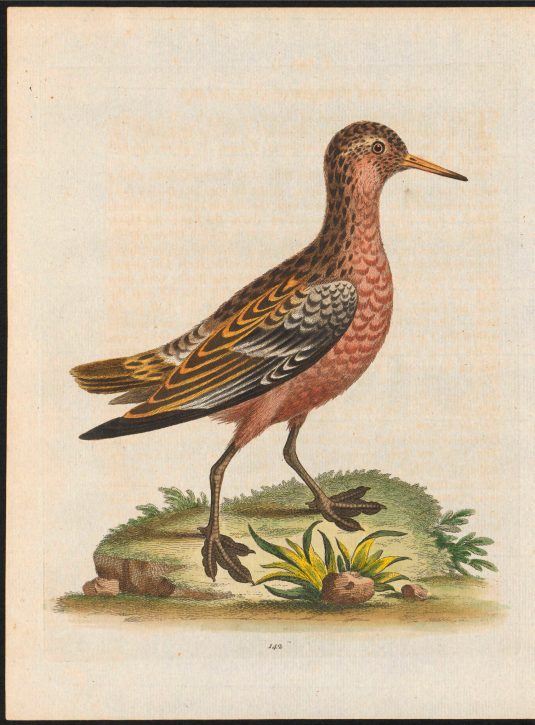

Here’s the stunning illustration of what he calls the Red Coot-Footed Tringa:

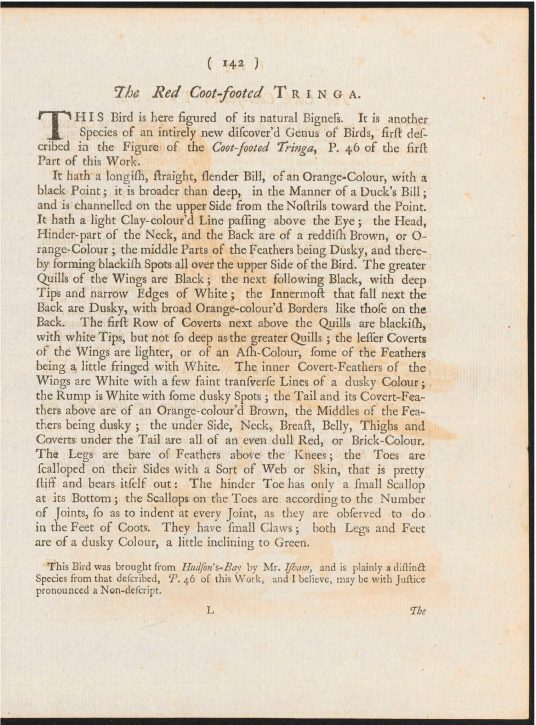

Here’s his written piece to describe it:

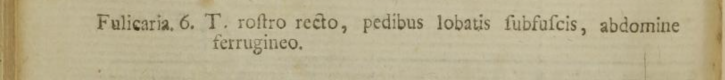

I find the mention of the Red Phalarope in Systema Naturae by Carl Linnaeus, from a few years later:

Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 146.

Red Phalaropes are only red in the Arctic, where they breed, without seeing people, and then they change plumage to grey and spend the rest of the year out in the ocean off West Africa and Chile, without seeing people. I send the details to The Orcadian newspaper and they do a nice write-up of my find:

What a privilege to spend time with it.

What’s a female in full breeding plumage doing in Westray in summer? The answer is their sex role reversal. It’s female Phalaropes which are brighter coloured, compete for males, lay eggs and then leave the males to bring up the chicks while they fly south over the ocean. It must be on its way for a year on the ocean waves and stopped here for a brief time to refuel, having left its male and chicks to fend for themselves in the Arctic.

As the sun gets lower, I see it fly powerfully around the pool and then set off across the Atlantic. I watch it until it’s out of sight.

I wish it well and thank it for its company.

And the Dunlin? I did get a photograph of a Dunlin, but that can wait for another day.

Have you seen a Grey Phalarope? What do you think of my find?

Feel free to leave a comment or subscribe to my blog if you’ve enjoyed this post and want more encounters with the natural world – I’m also on social media. Thanks!