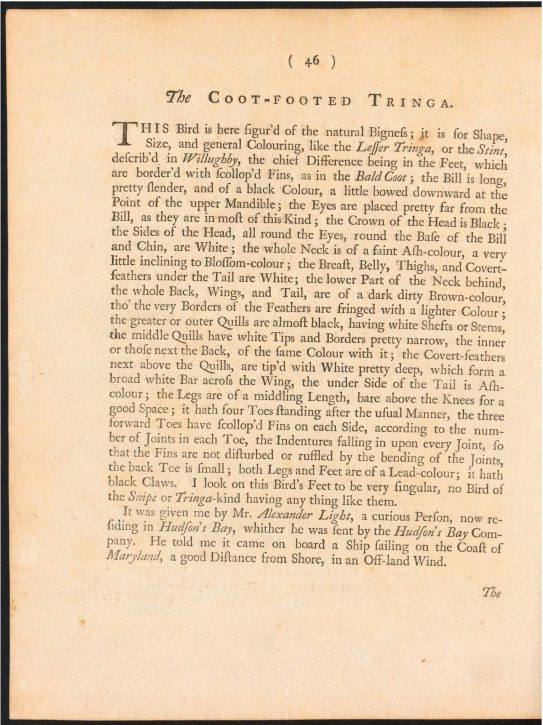

A Red-Necked Phalarope drops in

I see it from a distance initially. It’s always best to be lying on the ground in complete camouflage-pattern waterproofs with high powered binoculars here. Anything else and you’ll disturb most birds and they will fly.

It’s a Red-Necked Phalarope:

Aren’t they beautiful? I’d like to get closer, which should be simple, because they haven’t evolved to have a flight response to humans. Unfortunately, it’s surrounded by Dunlin, which have, and I suspect that when they fly, so will it.

I creep a little closer until I can see every feather:

That droplet of water, suspended in mid-air, makes the photograph for me. It’s there because the Red-Necked Phalarope shoves its head in the water looking for aquatic insect larvae and shrimps and the water runs off its head, down its beak and trickles back into the pool.

The Red-Necked Phalarope is mentioned in George Edwards‘s book A Natural History of Uncommon Birds from the 1740s:

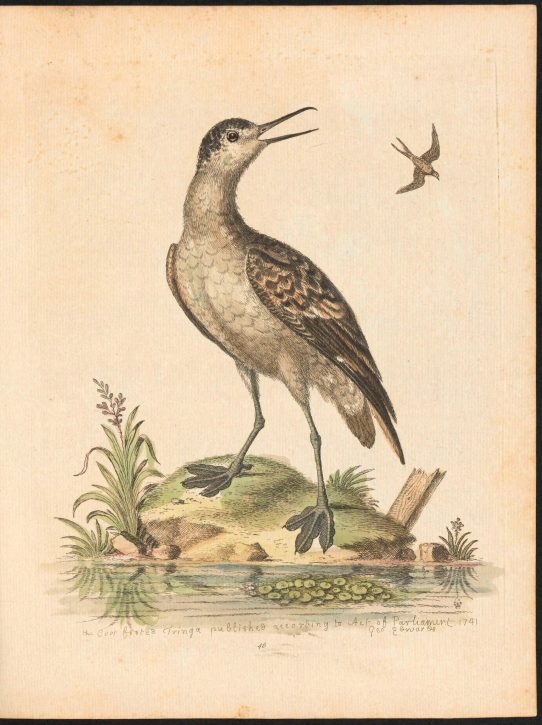

It’s referred to as the Coot-Footed Tringa. Here’s the illustration:

The illustration has definitely got the bill, the feet and the watery habitat right. I’m not convinced by the pose, though. It must have been hard to imagine based upon a preserved skin.

The text says it was found ‘A good distance from the shore’. That’s because, despite being a ‘wader’, Red-Necked Phalaropes spend their lives at sea when they’re not breeding in the Arctic:

An Arctic Skua comes overhead and the Dunlin fly and the Red-Necked Phalarope flies with them. I have a flask of tea and am sitting enjoying it when I almost drop it as I see it flying back on its own.

That beak is just like a bradawl. This is my favourite image. It shows the beak, the feet and its watery habitat perfectly:

To be alive to witness the wonders of self-replicating chemistry is a fabulous thing.

Thanks to everyone who shares that sense of awe with me every day.