The adventures of Dick and Titty at Brixham breakwater

There are long lenses galore at Brixham harbour. A flock of twitchers have arrived. They’re perched at the end of a jetty, eyes squinting in the sun, alert to any sign of a bird.

They are in search of the Great Northern Divers which have been overwintering in the bay of Torbay. I’m told there are 27 in the bay by someone more obsessive than me.

As they arrive one pops up directly in front of me. I love their strong horizontal beaks, their bulbous heads and their reptilian, scale-like plumage. I mean the Great Northern Diver, not the twitchers.

They are very handsome.

The pollution from this trawler isn’t. Surely that’s due an MOT? There’s the particulates of a thousand Golf Polos just there.

I move on to Brixham breakwater and there’s a Diver off the beach. I wait until it dives and then trundle down to the waterline and get as low as possible. My knees are wet waiting. It surfaces nearby and I get a shot of it flapping.

What thin wings they have for their chunky bodies. When they dive they use only their feet, unlike Puffins, which ‘fly’ underwater by flapping.

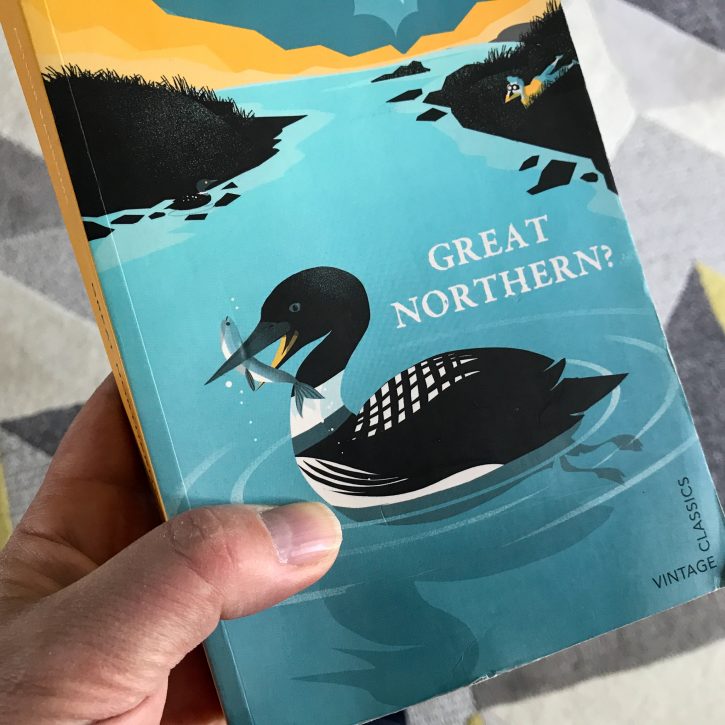

As Britain is in lockdown in everything but name I’m currently sat in an armchair reading. I’m catching up on a classic of many people’s childhoods which somehow passed me by. Maybe it was the obsession with describing the technicalities of sailing? Maybe it was the extreme middle class nature of the children? Maybe it was reading all about Dick and Titty’s adventures and trying not to snigger?

Whatever it was that put me off back then, it’s nice to catch up with Great Northern? by Arthur Ransome, author of Swallows and Amazons, now. Whatever his faults, or limitations, or the criticism hurled at him, one thing is clear; Ransome had a gift of expressing the lived experience of childhood which is timeless.

“The swimming bird, with one dive after another, had come nearly half-way from the island towards the place where Dick lay hid. He was getting a better view of it each time it came to the top of the water. Its head seemed very dark on the top, and the whole bird seemed even larger than he had thought at first sight. It dived, and came up a minute later with a fish, struggled with it on the surface, swallowed it, sipped water, and swam nearer still. Dick was puzzled, but he knew very well that nothing is more difficult to judge than the size of things seen at a distance through a telescope. The bird dived again. Dick watched the spot where it had gone under, but it must have been swimming straight towards him. When it came up it was no more than thirty yards off, and Dick was so startled that he nearly shouted aloud.

‘It’s a Great Northern,’ he said to himself, and had added it to his list before he remembered that Great Northern Divers did not nest in Great Britain.”

It may be one you’ll enjoy in glorious isolation.

What I’ve learned from reading it is that I’m still living my childhood joy in the natural world, and that can only be a good thing.

More from Brixham

Shag again There are two species of Cormorant found in the UK, the Common Cormorant and the Shag. This is a Shag.… read more

Shag again There are two species of Cormorant found in the UK, the Common Cormorant and the Shag. This is a Shag.… read more Rock on concrete There's a Rock Pipit on Brixham Breakwater. I love seeing them here, as they skit along the top of the… read more

Rock on concrete There's a Rock Pipit on Brixham Breakwater. I love seeing them here, as they skit along the top of the… read more Waiting for the change I can't wait to see some Mediterranean Gulls in breeding plumage. Until then, I'll just have to appreciate how handsome… read more

Waiting for the change I can't wait to see some Mediterranean Gulls in breeding plumage. Until then, I'll just have to appreciate how handsome… read more Little mover The scientific name for the Pied Wagtail is Motacilla alba. Motacilla means 'Little mover' and alba means white. This one… read more

Little mover The scientific name for the Pied Wagtail is Motacilla alba. Motacilla means 'Little mover' and alba means white. This one… read more Cuttlefish for breakfast When I've visited Brixham harbour over the past few years and walked down the historic slipway near the breakwater I've… read more

Cuttlefish for breakfast When I've visited Brixham harbour over the past few years and walked down the historic slipway near the breakwater I've… read more Sparrow I love seeing Sparrows. They were my gateway drug into wildlife conservation. They were almost the only bird which visited… read more

Sparrow I love seeing Sparrows. They were my gateway drug into wildlife conservation. They were almost the only bird which visited… read more A drip of water There's a drip of water on this Gannet's beak. It's just spotted a fish below, so it'll shortly be completely… read more

A drip of water There's a drip of water on this Gannet's beak. It's just spotted a fish below, so it'll shortly be completely… read more Buoyed I'm lying face down in fishy bird poo again and I'm swaying gently from side to side and up and… read more

Buoyed I'm lying face down in fishy bird poo again and I'm swaying gently from side to side and up and… read more The Crab and the Diver A trip to Brixham breakwater was a welcome break from writing, and organising my life. I love the Great Northern… read more

The Crab and the Diver A trip to Brixham breakwater was a welcome break from writing, and organising my life. I love the Great Northern… read more