Black Bulgar Pontefract cakes

How many people know what Pontefract cakes are? Surely not just people who live in Yorkshire? Maybe some people who live in Lancashire as well? Pontefract cakes are liquorice sweets made in the town of Pontefract in Yorkshire. This log looks like it’s covered in them.

It’s not; it’s a fungus called Black Bulgar, Bulgaria inquinans. Inquinans comes from the fact that it stains your hands if you handle it.

They’re beautiful shiny black buttons. They’re featured in my copy of British Fungi and How to Identify Them, which was worth every one of the forty pence I paid for it.

Here’s what the book says:

This is a curious and uncommon cup-fungus found occasionally about decayed stumps or vegetable refuse. It belongs to that important body of fungi, known as Ascomycetes, where the spores are generated in the interior of the cup. It has neither gills nor pores such as are indicated in specimens previously dealt with. Although dark and featureless its development is interesting; and identification is easy after once seeing it in its native habitat.

Ascomycetes? What are they? Ascomycetes are a type of fungus which produce their spores in a sack on their surface and shoot them out, giving them the common name of ‘spore shooters’. The asco of their name is from the Ancient Greek for sack or wineskin, which is the shape of the microscopic structures which enable them to reproduce. Ascos (as I’m going to casually call them) include truffles, yeasts, and cup fungi, so we get bread, beer, cheese and penicillin from them. You can also get a nasty case of thrush or aspergillosis, too, so it’s not all good news.

Black Bulgar is covered in distinctive microscopic spore-shooting sacks.

The cups are from one to two inches in diameter, and fairly regular in the early stage of growth; when expansion occurs, the cup vent gradually widens to the appearance of a shallow saucer which in wet weather holds its quota of rain water. As a rule, the margins remain upturned, but examples may be found in which cups become flat or convex. The fungus is smooth, has no hairs, warts, or scales, and feels much like rubber. The flesh is blackish brown, very tough, and will stretch before tearing. In wet weather it is slimy, but does not stick like gluten. Scarcely any odour can be detected from the Black Bulgar; but if burnt as stubble, it soon asserts itself. It is regarded as an esculent, but the taste is far from being pleasant.

I love the way an odour is described as ‘asserting itself’. This was written in the 1930s and I doubt that many people would be able to understand the word esculent now. Knowledge has also progressed, so please don’t eat it; it is no longer regarded as an esculent.

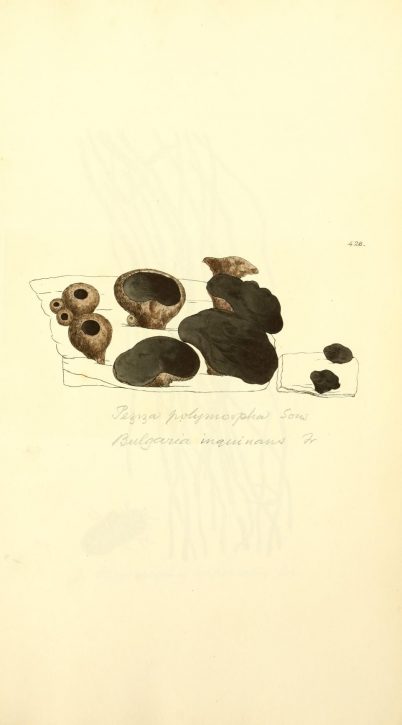

Here it is from James Sowerby’s Coloured figures of English fungi or mushrooms from 1797:

It’s great to feel part of a tradition of appreciating the natural world and adding to its understanding. Thanks for being on the journey with me.