Sparrowhawk

I can recognise a Sparrowhawk flying now: flap-flap-glide, flap-flap-glide. It’s a distinctive pattern.

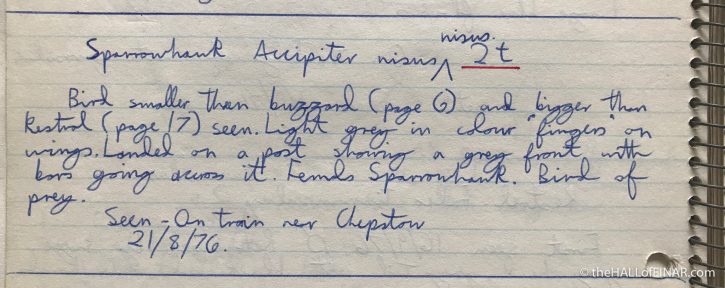

I saw one as a child from a train window and wrote about it in my childhood nature notebooks. Here’s my entry from 21 August 1976.

It’s the forerunner of this blog.

I occasionally see a Sparrowhawk near a busy A-road flyover near my house in South Devon and sometimes see one crossing six lanes of traffic to get to the old oak trees in the local Sainsburys. I’ve finally got a strong sense of the swooping motion they make. I also see one regularly burst out of the trees on the banks of the River Teign and cross over to an isolated area on the other side of the River to roost at dusk.

I’ve rarely had a decent photo opportunity. I don’t have the sort of garden that they would regularly visit on the lookout for birds drawn to a garden bird-feeder.

Birds of prey are also a lot less common than they should be because of persecution by landowners. They are routinely shot and trapped, even while satellite tagged, and their nests are destroyed. Getting the evidence to convict the culprits is always difficult and this country lacks vicarious liability. Landowners employ gamekeepers to kill our natural heritage and yet the instigators are completely immune from prosecution. A good example is that Elizabeth Windsor, known as The Queen, owns the Goathland estate as part of the Duchy of Lancaster which provides a private income to her. It is leased to a shooting company called W&G LLP, who contract with a Scottish agency, BH Sporting, to manage the land. They employ three gamekeepers, one of whom who set an illegal cage trap with three Jackdaws and trapped and killed a Goshawk on camera this year.

A rare goshawk has been trapped and killed by a masked man on the Queen’s grouse moor in North Yorkshire.

— Ban Bloodsports on Yorkshire’s Moors (@stoptheshoot) July 20, 2020

It is a clear illustration of how deeply ingrained bird of prey persecution is on grouse moors when not even the Queen’s wildlife is safe from criminals destroying it. pic.twitter.com/2e0bwWRD4M

The Goshawk is one of the UK’s rarest birds of prey with only 300-400 pairs left. They have faced centuries of persecution which led to the bird being extirpated in the UK by the late 19th Century.

We need to change the law so that landowners like Elizabeth Windsor are held liable and her estate prosecuted for the more serious crime of conspiracy to commit wildlife crime. Her estate has clearly contracted with a company which employed a masked man to carry out illegal acts to maintain the profitability of grouse-shooting. Without conspiracy and organised criminality against birds of prey there wouldn’t be the numbers of Grouse to make a profit: crime is an essential part of their business model.

I’ve never seen a Goshawk.

Another bird, the Hen Harrier must be the most persecuted bird in Britain. That includes being shot and killed on Elizabeth Windsor’s Sandringham Estate.

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2007/nov/07/monarchy.wildlife

Harry Mountbatten-Windsor, known as Prince Harry, was questioned, about the illegal killings, as he was the only one out shooting with a friend and a gamekeeper at the time, but the result was ‘Police are not seeking anyone else over killings’. I’d get six months in jail or a £5,000 fine. Landowners? Royalty? Nothing.

Sparrowhawks have been similarly persecuted. Nearby is the town of Moretonhampstead on Dartmoor. In 1207 King John granted a weekly market and an annual five-day fair to Moretonhampstead for the annual rent of one Sparrowhawk per year. Birds of prey have been pests, playthings or currency.

I’ve seen pigeon corpses at the Town Quay and thought Sparrowhawks the most likely culprit. It was late one evening, when walking down a depressing alleyway bordered by the rail line and a security fence for the local industrial estate that I heard it. There was a very high pitched ‘peeping’ of a bird in distress. Then I heard the fluttering of wings. Due to the gloom it was a while before I spotted it: a Sparrowhawk had caught a Feral Pigeon and had it in its claws.

Naturally I had my camera with me. You can’t take photographs without it. I sank to my knees, slowly, carefully, with the watchful yellow eyes of the Sparrowhawk eyeing me suspiciously. Then I lay down on the dirty tarmac, at eye level with the struggling birds and took a shot:

First to go was the Pigeon’s head. Then the breast feathers were meticulously removed.

It was very wary of me, but I lay motionless as the evening became darker and darker and the light became difficult to see. I was there for an hour.

As I lay there I heard a man behind me say “You all right chap?” He was holding a can of cider and a roll-up and I was grateful for his concern. Unfortunately the Sparrowhawk dragged the Pigeon away into the undergrowth and I decided to retreat.

When it comes to wildlife, the real issue we have in this country is land ownership. If you own the land you think you have the right to use it and do what you want with it. The problem is that it contains our communal wildlife wealth, and that shouldn’t be the landowner’s to dispose of as they see fit. We should all own the land and treasure the natural world it contains.

As I walk home, full of joy and despair, the moon looms large in the sky.

What an amazing wild world.