A Grayling

I’m trying to have a relaxed breakfast but there’s too much to see. I want my Italian coffee and croissant but I can see a butterfly fluttering around on the rocks and walls of the ruined buildings in the Rifugio della Rocca.

I have no idea what sort of butterfly it is. I can’t say I’ve ever seen it before.

It’s a master of camouflage. It’s also very confident in its abilities because I can get really close to it and it doesn’t move. It’s also doing something really weird; it’s twisting its body so that the wings lie flat against the stone. I’ve not seen that before either.

Back home I get my trusty 1939 butterfly book out; the one I bought for 30 pence decades ago with the stunning colour plates and comprehensive text: A Butterfly Book for the Pocket by Edmund Sandars.

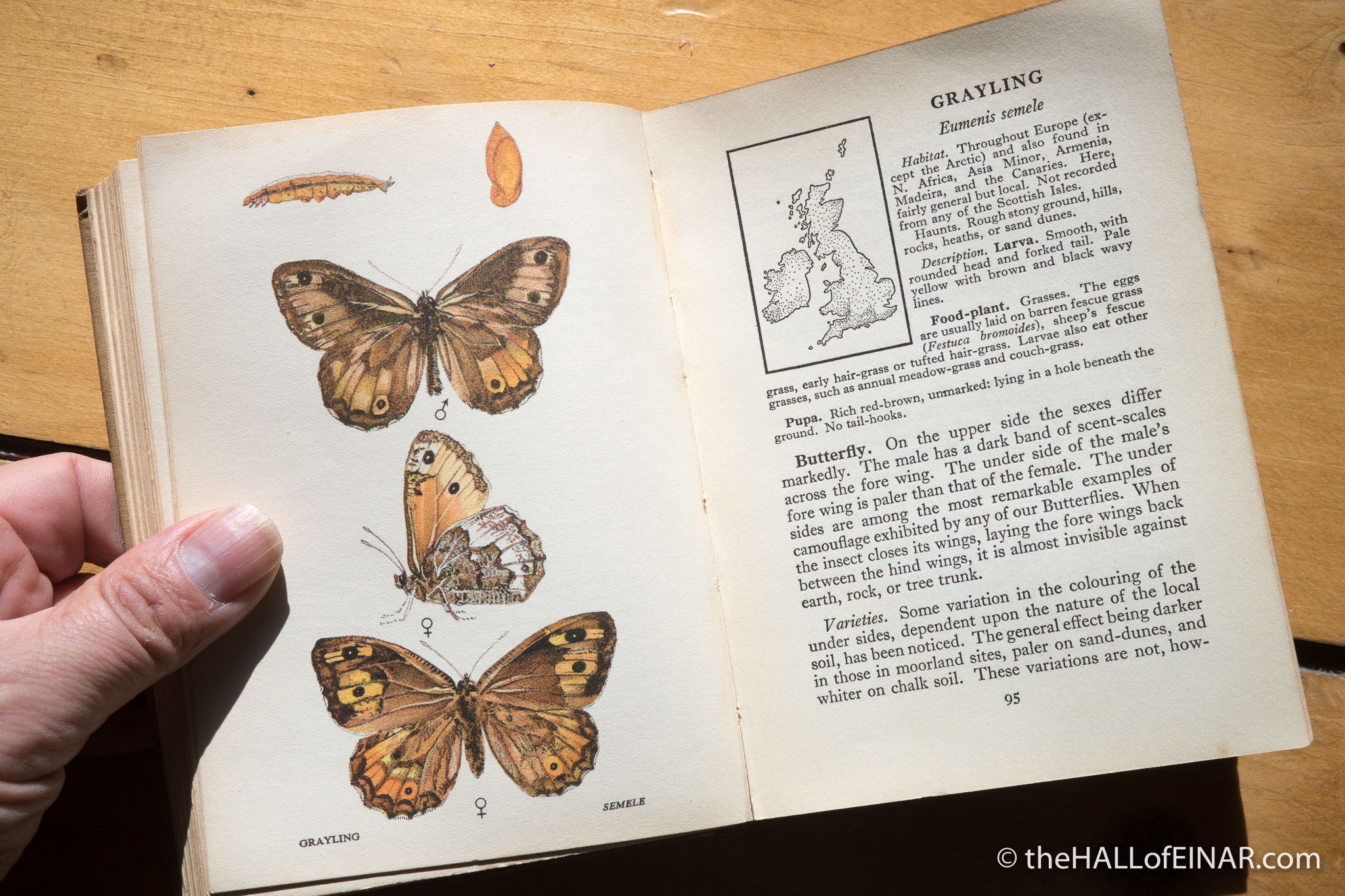

I turn the pages and decide it looks like a Grayling, Eumenis semele.

My book says: “Haunts. Rough stony ground, hills, rocks, heaths, or sand dunes.” That sounds right.

“The under sides are among the most remarkable examples of camouflage exhibited by any of our Butterflies.” Steady on Edmund, don’t get carried away.

“When the insect closes its wings, laying the fore wings back between the hind wings, it is almost invisible against earth, rock or tree trunk.” Okay, he has a point.

He continues: “The Butterflies behave unusually in several respects. They rarely fly unless disturbed, and then make a short swift flight of some dozen yards and then again settle, seeming completely to vanish. Their main need seems to be invisibility. Their likeness to a stony or bare spot of earth is wonderful, and they take advantage of this by settling on a suitable background, closing the wings, with the fore wings laid back between the hind. They even turn over sideways so as to avoid casting a shadow.”

So that’s their game, turn sideways so you don’t cast a shadow. I wonder how long ago a Grayling with a curious habit of lying down on one side was hatched and ended up inheriting the Grayling species, when all the others with large shadows got discovered, eaten and died out?

Edmund Sandars was quite the artist:

I also check UK Butterflies and find they say “This butterfly also has a curious technique for regulating body temperature by leaning its wings at different angles to the sun.” That’s a different explanation entirely for its behaviour. They also call it Hipparchia semele.

I look for some early records of the Grayling and find it in The Papilios of Great Britain from 1795 where it appears to be called the Great Argus and not the Grayling at all:

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/103670

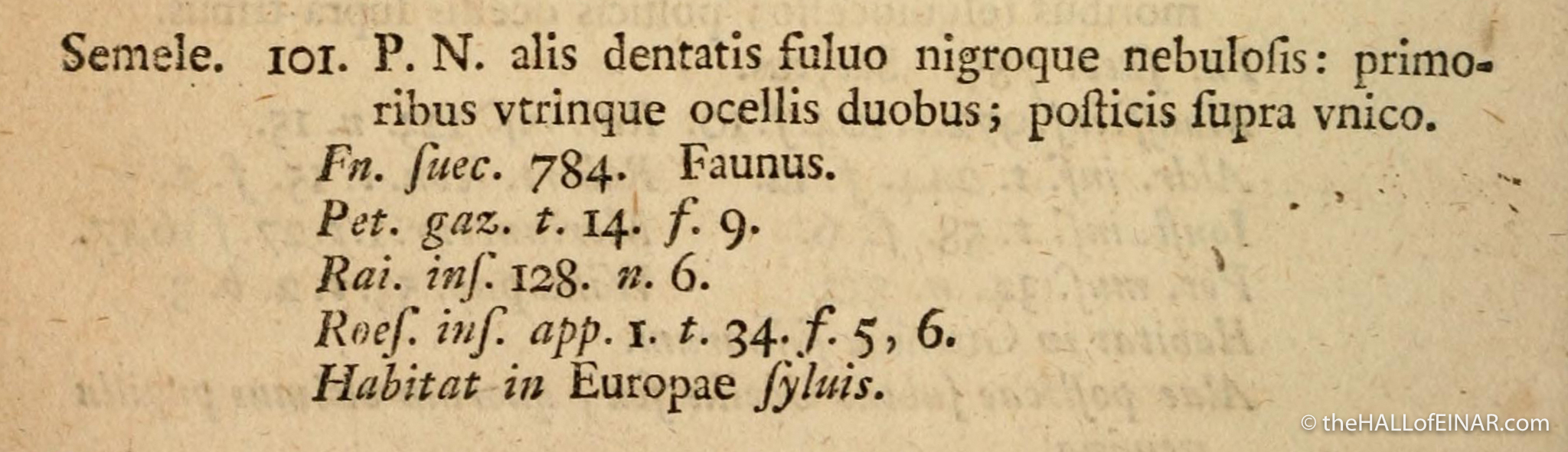

An earlier record of the Grayling is in Carl Linnaeus’s classic book Systema Naturae from 1758 which forms the basis of all scientific naming of natural life: Caroli Linnaei … Systema naturae : per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. It’s a classic because it was Linnæus who published names with binomial nomenclature, or two names; a genus, like Homo and a species, like sapiens. He was a Swedish man who published in Latin.

Here’s the entry for the Grayling butterfly Eumenis semele in his book:

I think it would cost me more than 30 pence to buy a copy, so I’ve accessed it here: http://www.archive.org/stream/carolilinnaeisys12linn

Linnæus is so important to the naming of living things that just the letter ‘L’ next to it is enough to tell everyone that the binomial name is the one that he gave it originally. How cool is that? To be recognised instantly by every one of your colleagues by a single letter of your surname for the rest of time?

That’s not the only thing which makes Linnæus amazing though. For every species there is a type specimen. It’s the dead body of the living thing, preserved, which is described with a clear indication of how it’s different from other similar species. What’s the type specimen for human beings then? It’s the mortal remains of Carl Linnæus. He is the very definition of Homo sapiens. If we want to check whether a living being is human or not, we have to compare them to Carl Linnæus for the rest of time.

Then the butterfly was gone, although not very far, and my coffee was cold.

I have a butterfly mind.