Peregrines v Buzzard

A bit of daily exercise means a walk up the hill and back. I’m trying to avoid the Grand Old Duke of York though, as there are probably a few coronavirus-infected people in his 10,000 men.

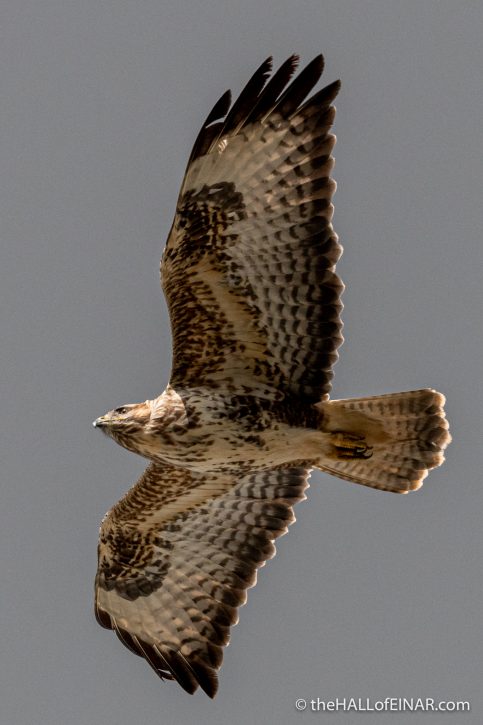

This is one of our local Common Buzzards, taken a few weeks ago:

As we walk up the hill we spot a Common Buzzard. Then we spot a Peregrine Falcon. Then we spot another Peregrine Falcon. At the risk of appearing episodic, what happened then was the Peregrine Falcons carried out a dramatic joint attack on the Buzzard by stooping from above and swooping down and then up, narrowly missing it.

On one attack the Buzzard turned completely upside down and bared its claws as a defence against the Peregrine. Obviously I didn’t have my camera with me, despite my profoundly held belief that you should always take your camera with you, even to the supermarket. These are different times.

Back home I do a bit of research and find that this Peregrine behaviour is only known from one individual female and its mate in Exeter.

It’s the pair at St Michael and All Angels Church in Mount Dinham, Exeter.

This sounds about right:

Extreme territorial aggression by urban Peregrine Falcons toward Common Buzzards in South-West England

I begin to read the paper’s extract:

Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) breeding on a city centre church in Exeter, in the south-west of England, have been studied in detail since first occupation in 1997. During this period, changes in both male and female falcons have been recorded. Following the arrival of a new female Peregrine in 2009, a dramatic change in behaviour towards Common Buzzards (Buteo buteo) on passage over the city was noted. Buzzards flying over Exeter are attacked by the falcons, especially so when in proximity to the church. We have attempted to document these attacks through our own observations, with additional information from local residents and wildlife organisations. Further records have come from veterinary surgeries and wildlife rehabilitators regarding injured buzzards found in the city. This paper documents the extreme levels of territorial aggression as demonstrated by the pair of Peregrines during cooperative attacks on Buzzards. We reveal this unique interspecific behaviour by summarising the number, frequency, timing and outcome of attacks undertaken over an eight-year period. We describe and illustrate the strategy employed by the Peregrines during a typical attack, plus consider implications on breeding productivity and the future scenarios should one of the current pair be replaced.

The paper describes 70 Common Buzzards being downed over the city of Exeter by Peregrine Falcons. Wow! I don’t use exclamation marks (or ‘screamers’ as newspaper editors called them) without good reason. That’s amazing. It describes Buzzards migrating high, very high, over the city being spotted by the female Peregrine who would abandon nest with eggs or chicks and spend ten minutes flying higher and higher, followed by her mate, so she was above the Buzzard and then attacking. What was most effective was the twin attack, where one would attack, the Buzzard would turn itself upside down to defend itself and as it got the right way around would be hit by the second Peregrine and tumble down to earth. Teamwork. Very effective teamwork.

In 2016, 92 attacks were observed, again with the additional help of watches by the Exeter University students, with six Buzzards seen knocked down and a further six found dead or injured in the city (Dixon & Gibbs 2016).

Here’s a PDF of the science: Article.

Buzzards are big and intimidating birds. They are not, as far as I am aware, a threat to Peregrines. It’s an unusual, even aberrant behaviour to attack them. It’s part of the variety of behaviours which genetics and evolution by natural selection throws into the mix from time to time. If it results in fewer Peregrines being produced in the resulting years with that behaviour then it will die out. If it results in eggs or chicks being put at risk while a parent is absent, or means the female catches less food, then other Peregrines with better adapted behaviour will thrive more.

I wonder whether the behaviour present in that Exeter female is something her offspring have inherited. We’re not too far away here. Maybe this female Peregrine is a daughter or granddaughter?

I’d expect Peregrine behaviour like that near to a nest site. I wonder where that pair are nesting?

The Buzzard was lucky and survived to fly another day, which is lucky for me, too.

Science. Brilliant, isn’t it?

Here’s the citation for the paper:

TY – JOUR

AU – Dixon, Nick

AU – Gibbs, Andrew

PY – 2018/12/01

SP – 232

EP – 242

T1 – Extreme territorial aggression by urban Peregrine Falcons toward Common Buzzards in South-West England

VL – 26

DO – 10.1515/orhu-2018-0031

JO – Ornis Hungarica

ER –